#writinginpublic comments welcome as chapter progresses

For Rosalyn Baxandall

Origin stories are a staple of historical narratives. Why did something happen when it did? How do those actions relate to events that came before? These are the questions that capture the historian’s imagination. This chapter takes up an oft-discussed question, what inspired a revival of feminist activism in the late 1960s? The stock answer relies heavily on a preceding event, the civil rights movement, with a specific document authored by activists in the freedom movement credited with inspiring women’s liberation.

As Rosalyn Baxandall noted nearly two decades ago, the origin narrative of women’s liberation has become a historical truism due, in no small part, to Sara Evans’ enormously influential history Personal Politics. Evans’ thesis “one of those rare scholarly arguments that has persisted virtually unchallenged for more than two decades” (Breines, The Trouble Between Us, p. 31), hinges on the reading of Sex and Caste at the December 1965 SDS Rethinking Conference which she describes as “the real embryo of the new feminist revolt.” Drafted in the fall of 1965 by Casey Hayden, a charismatic white southern SNCC worker and founding member of SDS, and co-signed by her friend and sister SNCC worker Mary King, Sex and Caste was sent privately to thirty-two women, sixteen black women, fifteen white women, and one Latina, virtually all of whom had significant backgrounds in SNCC.[Moravec, Revisiting Sex and Caste] The initial response to the Memo hardly harkened the pivotal place it has assumed in women’s history. Both Hayden and King recall not a single response to their missive.

Despite decades of subsequent scholarship that has challenged this singular origin point for women’s liberation, the stock narrative remains largely unchallenged. As Katie King noted in Theory in Its Feminist Travels all origin stories are interested stories.

Several consequences flow from the repetition of the standard account of the origins of women’s liberation. Contemporary feminism is built on an interpretation that centers white women’s emotional responses, their anger and frustration, to a movement dedicated to overcoming racism. This account also privileges rejection of the new left and civil rights over the dialogue that continued between activists who remained within those movements and women moving towards an autonomous movement. As a result, the role of civil rights ideology in influencing and shaping the formulation of feminist ideology has been de-emphasized. Paradoxically, while highlighting the split from civil rights, this origin story is used to legitimize women’s liberation as a significant social movement by providing its founders with activist credentials.

Origin accounts legitimize certain individuals as historically significant. Finally, this stock narrative creates narrow standards for inclusion, in the process creating exclusions. Who gets left out and why? What can digital analysis tell us about how this narrative took hold and how do the results of digital analysis help to shift that narrative once and for all.

Digital analysis of very early periodicals to emerge from women’s liberation has identified documents that appeared frequently during the formative years of women’s liberation, 1968 and 1969. Tracing the fate of those authors and documents in mass-market anthologies and subsequent popular and scholarly histories illustrates how the complicated history of the relationship between civil rights and the new left and women’s liberation has been narrowed down to one document. Retelling the story of the origins of women’s liberation in a way that incorporates those documents provides contemporary feminism with a history that reflects the ongoing “intellectual work” (Victoria Campbell Windle 266) that produced early feminist theory and re-centers the contributions of one group of African American women.

Digitally Documenting Influence

Sara Evans’ careful and nuanced account of women’s liberation relies on over sixty interviews she conducted with movement activists. While she cites new left publications and mainstream political magazines and journals, there is a curious absence in the sources she consulted for women’s liberation. She references only one periodical produced by women’s liberation activists even though the final two chapters of Sexual Politics cover the time period when these titles began to appear.

Movement periodicals have long been recognized as a significant source of information about women’s liberation. (Agatha Beins, Liberation in Print). Typed by activists, mimeographed, and mailed across the country, the earliest newsletters, journals, and newspapers have been described by one scholar as the “glue” that held the movement together. A precise listing of these earliest periodicals is difficult to find. Between 1968 and 1973, more than five hundred different feminist newsletters, journals, and newspapers were published in the United States. In the earliest years “feminism was primarily informal, grassroots, and highly localized. There were many small groups operating in relative geographic isolation and few institutionalized communication networks.” (Beins, Liberation in Print) Movement periodicals both document this local specifity, while revealing the networks that print communication facilitated.

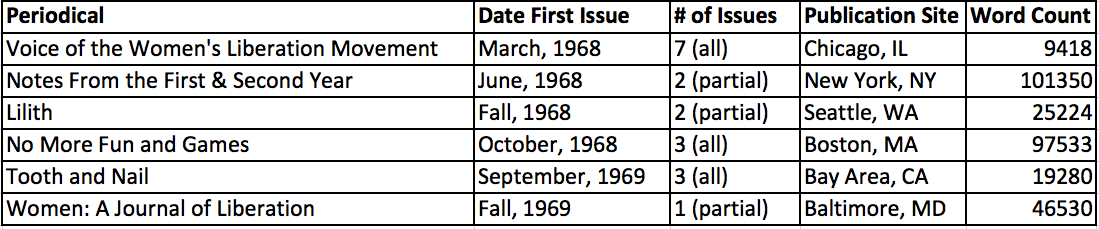

Of nine periodicals digitized by Reveal Digital’s Independent Voices collection, six were selected based on the quality of optical character recognition, word count and the number of issues, and geographical location for this basis of this study (table 1). A cut off date of Dec 1969 was established as the limit of the earliest phase of women’s liberation since 1970 is generally recognized as the year the movement went mainstream. (Dow, Watching Women’s Liberation).

Table 1. Texts included in this study

Voice of the Women’s Liberation Movement (VWLM) founded by Jo Freeman in Chicago has usually been viewed as the first autonomous periodical of women’s liberation. At its height, VWLM had a circulation of 2,000. The following summer, New York Radical Women compiled Notes from the First Year. While Notes from the Second Year produced by New York Radical Women contained works written and disseminated in 1969, but was not published until April of 1970, selling out as soon as it hit newsstands in New York City.[1] The Women’s Majority Union, an anarchist group in Seattle produced the inaugural issue of Lilith in the fall of 1968. Described by one scholar as “one of the earliest (and in some ways angriest)”[2] periodicals, Lilith lasted for only three issues but published several influential papers that were anthologized in later years. No More Fun and Games, out of Cambridge, Massachusetts offered the distinctive viewpoint of Cell 16’s members. There was such significant demand for the first issue of October 1968 that it was reprinted in February 1969 and by April of 1970, the print run reached 10,000. Tooth and Nail, a collaborative effort of women’s liberation groups within the Bay Area of California, probably had the lowest circulation and the least influence of the six periodicals, but it is included to offer important geographical diversity to this study. Finally, Women: A Journal of Liberation, edited by three Baltimore women, Donna Keck, Dee Ann Pappas and Vicki Ollard, became the first movement journal aimed at an explicitly national audience. Three thousand copies of the first issue were published. Women differed from other early movement periodicals not only in its slick design and production but also its thematic issues that contained academic essays.

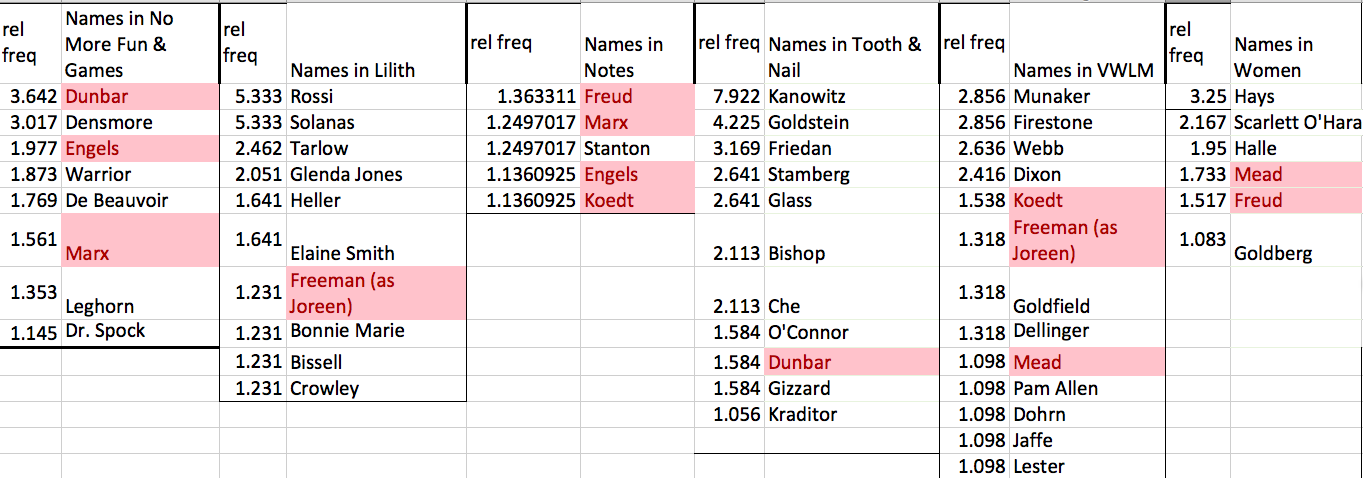

The influence of movement periodicals cannot be overstated in developing contemporary feminism, but the authors seldom hewed to scholarly practices of footnotes or bibliographies. The traditional means of documenting intellectual influence used by academics, which is to trace citations to specific texts, simply does not work. Of the six titles in my study sample, only one, Women: A Journal of Liberation published a significant number of articles that contained formal references. However, entity recognition, a form of natural language processing that locates people’s names offers a methodology for compiling a list of frequently mentioned individuals. That list can then be culled, using concordancing software which shows the context within the texts where names appear, to identify authors who are associated with particular documents, the goal of this study. Neither Hayden nor King appears on table 2 which lists the most frequent names extracted from the study sample of periodicals. Instead of Sex and Caste, these results suggest several other documents that were influential at the inception of women’s liberation.

Table 2. Frequently mentioned individuals in study sample of women’s liberation periodicals

Names extracted with Stanford NER then hand corrected and filtered for individuals who appeared at a relative frequency of greater than 1 per 10, 000 words. Red indicates a name that appears in more than one title.

The lack of extensive overlap in the lists across different titles calls into question the very notion that a single individual or written work should have a singular place in the origins of women’s liberation. The most common overlaps are male, Marx and Engels, indicating the great debt to the left in both No More Fun and Games and Notes from the First and Second Years. These results reflect few of the “big names” that scholars have so often credited as influencing women’s liberation. Simone de Beauvoir appears only near the top of No More Fun and Games, while Lilith championed the cause of would-be assassin Valerie Solanas. The influence of an earlier generation of academics is attested to through the prominence of Margaret Mead in the inaugural issue of Women: A Journal of Liberation and Alice Rossi in Lillith. VWLM in addition to reporting on the news of activists across the country served as a literature clearinghouse; a list of papers for sale appears at the end of each of the first six issues, accounting for many of the most frequently mentioned names. Reporting on the fights among various factions within women’s liberation also accounts for some of the names, especially Shulamith Firestone, who had yet to publish The Dialectic of Sex.

The names that appeared in other journals attested to their relatively local purview. Tooth and Nail was largely concerned with Bay Area events, although lengthy book reviews offer insights into what was being read. Concordancing software, which shows the context in which a name appears, clarifies that the presence of a name does not necessarily indicate great influence. Friedan appears in a negative review of The Feminine Mystique, while Kanowitz is mentioned throughout “a critical review” of his book Women and The Law: The Unfinished Revolution. Goldstein, Bishop and Stamberg were local New Left men who the women targeted in a protest against pornography in the Bay Area movement press. Similarly, Dellinger, the editor of Ramparts, was roundly condemned on the pages of Voice of the Women’s Liberation Movement, while Freud is invoked negatively in Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm and several other pieces that were reprinted in Notes from the First Year and Notes from the Second Year.

Three activist-authors appear on these lists. Roxanne Dunbar, a member of Cell 16 who edited No More Fun and Games, undertook a national speaking tour in 1969. Her essay “Class and Caste” and accompanying talk received a large amount of coverage in Tooth and Nail. While Dunbar is hardly absent from histories of women’s liberation, she is seldom given as much attention as New York-based Anne Koedt, who authored several early papers that appeared in Notes and were sold by Voice of the Women’s Liberation Movement. Freeman appears as the editorial contact for Voice of the Women’s Liberation Movement in Lilith and on the pages of her own publication. The overlaps in their appearances, in at least two periodicals, hints at the connections that existed between geographically distant groups within women’s liberation and to they way influence circulated; in person speaking tours, but also through print networks, especially reprinted essays in periodicals or sold as pamphlets. Dunbar and Freeman also did significant labor as editors, highlighting an important aspect of the creation of feminist theory that goes beyond mere authorship to incorporate contributions of individuals who focused on the dissemination of ideas in print.

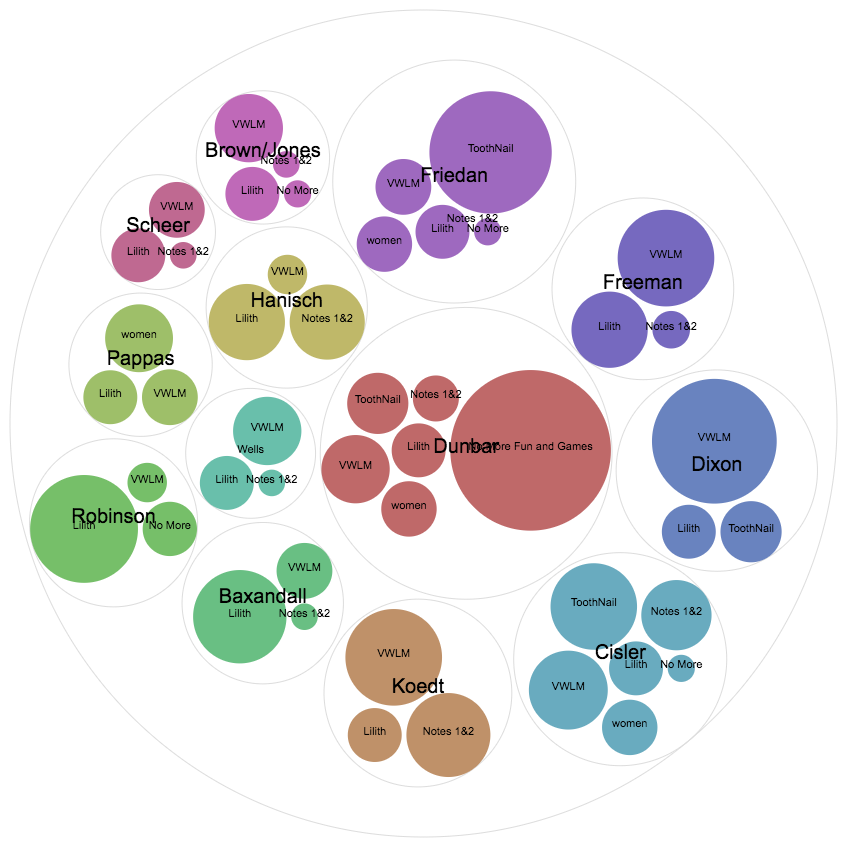

Amplifying this approach, looking beyond the frequency of an individual in a single title, to the dispersion of a single individual across the titles in this sample study is another way of capturing influence. Returning to the entity recognition results, there are thirteen activists names that appeared in at least three of the six periodicals.[4] Several of these women were both involved in civil rights movement and authored a well-known document providing a pool of potential parallels but also alternatives to Hayden and King’s Memo.

Names extracted by Stanford NLP program and hand-corrected using Lancaster Box to arrive at the relative frequency of individuals by title. Results visualized using Raw

Five of those women are associated documents that offer insights into the complicated dialogue that occurred between white women who remained tied to civil rights and the new left and those who advocated for an autonomous movement for women’s liberation. These documents provide a more satisfactory bridge between the two movements for several reasons, in addition to their presence in movement periodicals circa 1968 and 1969. Firstly, they are temporally closer to the formation of the movement itself, while Sex and Caste was written and first discussed some eighteen months before the first women’s liberation groups formed. These documents also evince the ongoing process of theorizing feminism that was produced by continual dialogue that occurred with women who remained connected to Civil Rights and the New Left, rather than offering a narrative of decisive splintering that is so strongly tied to Sex and Caste. Finally, a perhaps most significantly, one of the documents is authored by black women, providing a necessary corrective to the standard narrative that is overly rooted in white women’s experiences and emotions.

The Potential Documents

Jo Freeman (Chicago) “BITCH Manifesto” circa fall of 1968/winter 1969.

Freeman, a civil rights and free speech activist during her college days at Berkeley, went to work registering voters in the south during the summer of 1965 and stayed on as an organizer under the auspices of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). When she was exposed by the press in August of 1966, the SCLC removed her from fieldwork. That fall, she was sent to Chicago, where although the SCLC project ceased to function, Freeman continued to work in the new left. Freeman was part of the now infamous attempt by new left women to present their demands during the plenary session of the National Conference of New Politics held over Labor Day Weekend 1967 that resulted in a particularly condescending dismissal by the chair that reputedly led to the organizing of the first women’s liberation group in Chicago.

Freeman was well known for several essays she authored in 1968 and 1969 including The Bitch Manifesto. Like Sex and Caste, the BITCH manifesto compares gender and race. However, Freeman eschewed the tentative tone of Sex and Caste, which sought to raise more questions than it answered, and instead drew bold parallels between the epithets “bitch” and “nigger” and argued that women were “enslaved.”

“Like the term ‘nigger,’ ‘bitch’ serves the social function of isolating and discrediting a class of people”

Freeman equates the positions of “women” and “blacks” without discussing the uneven consequences that inhere by gender and race to failing to “conform to the socially accepted patterns of behavior.” The extended argument of The Bitch Manifesto is not that racism and sexism function in systemically analogous ways, but rather that in order for women to become liberated they will have to redefine themselves outside the confines of a male power structure that regards any deviance from prescribed norms as bitchiness. Her screed adapts the black pride slogan “black is beautiful,” to “Bitch is Beautiful” in order to convince women to rebel against the strictures of femininity. The Bitch Manifesto has been widely reprinted and discussed by scholars, but absent consideration of the way the manifesto illustrates white women’s appropriations of tropes of race (nigger, enslaved, black is beautiful) to legitimize their own status as oppressed individuals.

Written at roughly the same time as The Bitch Manifesto,“Toward(s) a Female Liberation Movement” (aka the Florida Paper) also reflected the influence of civil rights activists in shaping early women’s liberation ideology. Judith Brown and Beverly Jones (Gainesville, Florida) were longtime civil rights activists. Both women became involved in the movement in 1963, Jones through Gainesville Women for Equal Rights, a group that supported desegregation efforts, and Brown through the Congress Of Racial Equality (CORE). Brown’s fiancé had excitedly read the text of A Kind of Memo over the phone to her when he first encountered it in 1965. The Florida paper, however, was a response not to Sex and Caste, but to the 1967 Resolution on Women authored by the Women’s Caucus of SDS. Jones started the paper and it was completed with the assistance of Brown beginning to circulate by mid-1968 ( presented at the June 1968 SDS national council meeting) and fully completed in time for the Thanksgiving 1968 Women’s Liberation Conference held in Sandy Springs, Maryland.

Brown and Jones believe women and blacks are situated in a similarly oppressed position when considered in relation to the white man. “There is an almost exact parallel between the role of women and the role of black people in this society. Together they constitute the great maintenance force sustaining the white American male.” Consequently, they responded to the “socialist” and “third world” “verbiage” of the SDS women’s resolution in the language borrowed from black power. For exmaple, they excoriated the SDS resolution for “soft-minded NAACP logic” and dismissed its “Urban league” approach.

Although the Florida paper consisted of two parts attributed to individually to Jones and Brown, both authors relied on the same strategy of replacing race for gender. Substituting “white” for “male” and “black” for “female” suggests not an analogy between sex and race, as occurred in Sex and Caste, but an equivalency that leads to the appropriation of racial epithets for describing women’s status: woman as “some man’s nigger” and prominent new left women as “exceptional niggers.” Women who are married are the same as blacks who seek integration.

The thrust of the essay, adopted from civil rights, is that women need their own movement, not to remain as subordinates to the larger causes of the new left. The claim “People don’t get radicalized fighting other people’s battles” particularly adapts the insights of black power to women’s liberation. Just as whites could not liberate blacks and thus had to leave the movement, the only way women would become radical was to fight for their own liberation by leaving other movements.

The Florida paper provoked a considerable reaction. An anonymous member of Redstockings claimed “Everyone hated it. They said it was ridiculous” while Susan Brownmiller recalled that their “ heretical argument” attracted no one but Carol Hanisch and Kathie Sarachild an impression echoed by Hanisch. (In our Time 31) However, VWLM listed it as recommended reading

in the new left, and among women in civil rights. Lyn (Lynn) Wells (Nashville), a highly respected SNCC worker as a teenager,who was working for the SSOC, responded to Brown and Jones in “American Women: Their Use and Abuse.” . She eschewed racialized metaphors save for one instance of wage slavery, although she drew some “almost” parallels American women and slaves. Her emphasis is on the status women and black as exploited classes. Wells proposed that radical women hold their own meetings, but remain connected to the New Left.

VWLM in January 1969 carried an announcement of Wells’ activities: “The Southern Students’ Organizing Committee (P.0, Box 6403, Nashville, Tenn. 37212) has made women’s liberation one of the topics covered by their speakers bureau., Lynn Wells of SSOC is tentatively calling a Southern Radical Women’s Conference in February,

Carol Hanisch (NYC/Gainesville). “Personal is Political” February 1969. Hanisch was an activist in Mississippi during the summer of 1965 where she met Anne Braden and began working for her in the Southern Conference Education Fund (SCEF). In 1966 she began running the SCEF NY office, which she secured as a meeting place for New York Radical Women when the group formed in 1968, In early 1969, in response to a critique of consciousness-raising by Dottie Zellner, a civil rights movement veteran of Hayden’s cohort, Hanisch authored a memo that convinced the SCEF organization to send her to Gainesville for six months to organize a “freedom for women” project. That memo evolved into “The Personal is Political.” Hanisch, like Wells, views women as a potential group to be mobilized by the left, akin to workers and blacks. She eschews historical parallels, although she makes one reference to women as sex slaves.

Patricia Murphy Robinson (New York) A Historical and Critical Essay for Black Women of the Cities, written circa . Civil rights movement activist, an associate of Malcolm X, and a social worker. Although the essay was eventually attributed to collective authorship, earliest circulating version bore Robinson’s name. The essay laid out a history of black women’s oppression that traced back to slavery, while simultaneously opposing white women’s appropriation of racial metaphors, particularly that of enslavement.

Like Wells’ work with SSOC, Hanisch’s efforts in the SSOC were seen as consistent with women’s liberation. VWLMJan 1969 carried a note “The Southern Conference Educational Fund will provide subsistence to Carol Hanisch, formerly of the New York Radical Women’s Group, for six months this year to “explore the organizing potentials in the South for Women”s liberation. Her work will include. 1) talking to other movement women informally and in conference; 2) experimenting with a caucus in existing SCEF projects; 3) initiating a women’s project–probably with poor white and black women.”

Telling Different Stories

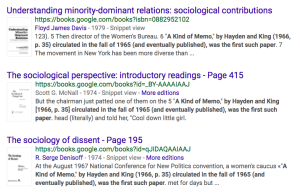

Sara Evans introduced Sex and Caste to a wide historical audience as the lynchpin that connected women’s liberation to earlier new social movements in 1979. However, digital analysis of texts published between 1967 to 1978 suggests that three “viral” sentences in works published had already established the interpretative framework that continues to surround Sex and Caste. These authors emphasized the identity of the documents’ authors, the affective consequences of its circulation, and its position of primacy in analyzing systemic sexism in civil rights and the new left. Following these viral sentences, which are replete with errors, subsequent scholarship has rooted the origins of women’s liberation in whiteness, occluded the contributions of black women, and conflated primacy with influence.

Google Books and JSTOR offer only twenty-one mentions of A Kind of Memo in texts published between 1966 to 1978 [for comparison Juliet Mitchell’s Women: The Longest Revolution (December 1966) appears in 43 items in the same sources]. Within this relatively limited discussion, frequently repeated sentences began to establish the historical framework that continues to surround Sex and Caste.

The first sentence appeared in an essay published in a special issue of Motive magazine written by Linda Seese, a Freedom Summer participant who also was involved in women’s liberation in both Toronto (circa 1967) and Chicago (circa 1968).

In the fall of 1965, Casey Hayden and Mary King, two white women from the South who had been very active in SNCC and ERAP for years, wrote an article on women for the movement in the now-defunct journal, Studies on the Left.[2]

This framing of Sex and Caste emphasizes the whiteness of the authors, while also linking Hayden and King to civil rights, via SNCC, as well as the SDS offshoot, ERAP, although only Hayden worked for that project. It erroneously identifies the intended audience, the piece was a private memo, not one written for publication, as well as the journal in which it eventually appeared, which was Liberation not Studies on the Left.

Seese’s essay, which initially appeared in a special issue of Motive dedicated to the X, was subsequently reprinted

An expanded version of the special issue of Motive appeared as a mass-market anthology in 1970 spread Seese’s interpretation even further as did Robin Morgan, who used an almost verbatim sentence in the introduction to her blockbuster anthology Sisterhood is Powerful (1970).

In 1965, Casey Hayden and Mary King, two white women who had been active in SNCC and other civil-rights organizations for years, wrote an article on women in the Movement for the now-defunct journal Studies on the Left.

This framing continues down to 2016.

Casey Hayden and Mary King, two white women also active in SNCC, wrote an article on female activists for the journal Studies on the Left.

If the identity of the authors, their whiteness and their movement credentials, was the centerpiece of Seese’s contextualization of Sex and Caste, other authors were more interested in the outcomes it prompted. Marlene Dixon, a sociology professor made famous by student sit-ins protesting the University of Chicago failure to renew her contract, emphasized the affective consequences of Sex and Caste as she explained women’s liberation in Radical America’s issue on the movement (February 1970)

Casey Hayden and Mary King rousing a storm of controversy for their articles in Studies on the Left and Liberation

Here, the identities of King and Hayden and their credentials are omitted; what matters is the reception of their ideas, which are deemed controversial and credited with provoking a storm on the left. Dixon’s essay was quickly reprinted in yet another popular anthology of 1970 From Feminism to Liberation and in an academic sociology anthology.

This interpretation persists today as well “The controversial memos censuring sexism in the movements and society that white SNCC organizers Mary King and Casey Hayden had written” (2007) and “catalogued by Hayden and King in their provocative memo.” (2008).

Finally, in 1973, a footnote in Jo Freeman’s essay on the origins of women’s liberation emphasized the primacy of A Kind of Memo.

A Kind of Memo,” by Hayden and King (1966, p. 35) circulated in the fall of 1965 (and eventually published), was the first such paper.

While Freeman also notes that women’s liberation did not emerge as an autonomous effort until 1967, by emphasizing that this was the “first” paper “on women,” she contributes to the conflation of primacy and influence. Freeman’s essay was reprinted in academic sociology texts solidifying the temporal place of Sex and Caste. Given this extensive gap between the first public discussion of Sex and Caste (December 1965) and its widespread dissemination (April 1966), what evidence exists to support the interpretation that Sex and Caste was a significant document in the earliest years of women’s liberation? Was controversy the most important outcome? Were their subsequent documents that continued to work started by Sex and Caste that might offer insights into the connections between women’s liberation and other social movements?

[**] Tobis quoted in Lynne Olson, Freedom’s Daughters, Roxanne Dunbar, Outlaw Woman

[*] Katie King, Theory in Its Feminist Travels: Conversations in U. S. Women’s Movements

[1] Michelle Moravec, Revisiting “A Kind of Memo” from Casey Hayden and Mary King, Women and Social Movements, March 2017.

[2] This account contained several errors. The essay did not appear in Studies on the Left. Hayden was involved in ERAP, but King was not.

[3] Corpus includes Voice of the Women’s Liberation Movement, Lilith, No More Fun and Games, Tooth and Nail, Notes from the First Year and Notes from the Second Year, Women a Journal of Liberation through the end of 1969.

[4] Named entity recognition was used to extract names that provided the basis for a frequency list that was manually compiled. Individuals were identified as activists within the movement as opposed to historical figures or contemporaneous individuals who were peripheral to women’s liberation.

[5] Peter Filene, Him/Herself

[6] Unlike a kind of memo Brown and Jones labels their contributions as part 1 and part 2 attributed to individuals. ” Part 1 Written by Beverly Jones [did it circulate on its own Toward a Female Liberation Movement, Part I. New England Free Press, 1968.]