Paper given at Keystone Digital Humanities Conference July 24, 2015, cross posted on the LSE Impact Blog

How Dataviz Changed (how I think about) History (of women’s liberation)

Almetrics is a buzzword I’ve shameless repurposed to give some cachet to my desire to find women who contributed to this academic artifact called “feminist theory” but who have largely been relegated to peripheral roles in the history of its development. Having already done a highly subjective project in this vein, the current iteration takes up the question I posed at the end of Unghosting Apparitional Lesbian History. What about all the other Bonnie Johnsons?

What would a historian’s altmetrics look like? How can we measure the impact of people in the past? My community clustered under what we call “women’s liberation” in the US is represented both in print and in person. I looked at anthologies from 1970, monographs from 1975-1981, an academic journal, and a central conference, The Scholar and The Feminist (1974-1984).

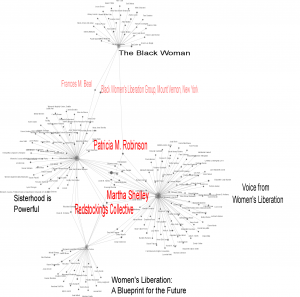

In 1970 women’s liberation went mainstream, and publishing houses jumped on the bandwagon, offering not one, but four mass-marketed paperback anthologies. Of those, Random Houses’ Sisterhood is Powerful is the best known both for its slogan and iconographic cover. Leslie Tanner’s Voices from Women’s Liberation, which came out under the New American Library imprint aimed more at the movement itself. Beverly Guy-Sheftell notes that the papers within “were read and circulated in women’s ‘consciousness raising groups.’” Voices from Women’s Liberation also explicitly connected women’s liberation to its historical antecedents and contained a considerable amount of material from the 19th century woman movement that Tanner hoped would correct the history “man” had “cheated” women of. Ace Books, a division of the soon to be defunct Charter Communications, published Sookie Stambler’s collection, Women’s Liberation: A Blueprint for the Future. All three of these white women were active in radical women’s groups in and around New York City when they put their anthologies together.

Rivaling the influence of Sisterhood of is Powerful, was Toni Cade Bambara’s The Black Women published by Penguin in 1970. Weary of hearing there was no market for books by Black women, Cade knew that the anthology would “open the door and prove that there was a market,” but she also wanted a book that would “fit in your pocket and be under a dollar.” While only Sisterhood and The Black Woman are still in print today, a quick search of Google books or the Hathi Trust reveals that essays from all four anthologies are still quite frequently cited. As one member of the founding generation of women’s studies, who also participated in women’s liberation, noted, these anthologies were “the required reading” for the first courses taught in universities across the US. By the time of my own women’s studies education in the late 1980s, they’d been reduced to slogans and buttons, although I avidly sought them out combing through used bookstores wherever I went. Through the years, as I moved, I schlepped them with me. I pulled my battered and torn copies of the shelf for this project.

Scraping from online catalogs and then digitizing when I had to, I took the table of contents, separated titles and authors, and put them into a spreadsheet that I then pulled into Palladio where I explored the relationships. Although James P. Dansky argument that “publishing became the fiber that bound together a community that was otherwise divided along lines of race, class, ethnicity, and sexuality” might be rather optimistic, these anthologies placed in the hands of hundreds of thousands of women texts that previously circulated only among small groups. Looking at the anthologies as a snapshot of women’s liberation print culture at its very broadest, I was curious about which authors or essays received the widest dissemination.

Only three authors of the almost two hundred are represented in three of the four anthologies, the Redstockings Collective, Martha Shelley, and Patricia M. Robinson. The Redstockings were an early, influential New York Based radical feminist collective. Martha Shelley was among the first radical lesbians in women’s liberation, and Patricia M. Robinson was one of the first black women to write about women’s liberation (and a member of the group cited here as “Black Women’s Liberation”). The Redstockings Manifesto, a widely circulated articulation of the principles that would become known as radical feminism, suggested to me, following other work I’ve done on feminist manifestos, to look at the piece attributed to Robinson, “A Historical and Critical Essay for Black Women” as a manifesto would, I argue, function as one. If in 1970 the two pieces are of equal influence, at least as measured by inclusion in these anthologies, what happens over time, which after all is what historians are interested in?

Using the BYU Corpus Interface for Google Books I scraped the metadata for any references to “Redstockings Manifesto” or “A Historical and Critical Essay for Black Women” to create the visualization below.

The Redstockings Manifesto has been, and continues to be, more referenced than “A Historical and Critical Essay for Black Women.” The trend for Black women is disturbing in that it is waning as Redstockings is increasing. Does this indicate that Black Women is on its way out of history while Redstockings is more firmly establishing its placed within? Let me be clear. The work I’ve started to trace here and the women who wrote it have never been completely taken out of the narratives of history. Dedicated scholars have highlighted them, most notably M. Rivka Polatnick “Poor Black Sisters Decide for Themselves: A Case Study of ’60s Women’s Liberation Activism” (1991). Polatnick, also a participant in women’s liberation, wrote specifically to recover the women who had been left out of histories because they “fought” for women’s liberation “in other contexts.” Similarly, Rosalyn Baxandall argued for “Re-Visioning The Women’s Liberation Movement’s Narrative” as the title of her 2001 essay declared.

And yet still another answer exists. The data viz I showed you initially is a fiction. The first I produced did not show what I knew to be so, that “A Historical And Critical Essay for Black Women” appeared in more than one anthology.

Back to my spreadsheet I went where I discovered that variations in the title of the essay and in the author credits obfuscated the connections, as well as those for the other two central essays by black women Frances Beal and Maryanne Weathers. I share this not to reveal my own sloppy data, but to highlight the difficulties of doing this kind of visualization. After regularizing titles and author names, I created a dataviz that I showed you with the links. I pulled the dataviz into inkscape and inserted all the variations of names and titles.

This makes for a messy looking dataviz and that is precisely my point. If I had not known my sources so well, I would have drawn erroneous conclusions. In addition to know your data, an important point in working digitally, I want to also ponder what the messiness of my data means for the marginalized. It seems strange to me that there is such variation in their names (although I will note that this happens to white women as well). However the consequences for writing history of marginalized women are more disastrous because the numbers are already so low. I expect some shakeout in data, but what if what gets lost is the lone black woman’s voice?

I also began to wonder how it was even possible for such variation to exist. How could the editors make such mistakes? I am of course not the first to notice the presence of these women in the anthologies or the errors in the names. Katie King, in Theory in Its Feminist Travels, published twenty years ago, discussed this very point. King concludes “there is a sense of the obligatory but minimal inclusion called tokenism” precisely because these women are not “structurally ‘at the center’ of women’s liberation. I found King’s point provocative. How could digital history answer the question of how central were these authors to what we now call women’s liberation?

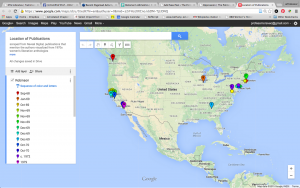

Turning to a print expression of the movement that is far more grass roots than mass market anthologies, I decided to look for Robinson in the many periodicals that developed out of women’s liberation. Reveal Digital has provided me with uncorrected OCR, machine-readable corpora consisting of over 6000 issues of periodicals from the Left. Here I searched all variations of Robinson’s name. I visualized this metadata and then for comparison repeated the process with the names of the other two black women who overlapped anthologies to visualize the spread of their writing.

Robinson’s work was definitely known within women’s liberation across the country prior to the appearance of any of the anthologies. While the essay was first published in 1969 Journal produced by the Boston based Cell 16, called No More Fun and Games, there is ample evidence of Robinson in women’s liberation prior to that date. In the Fall 1968 Lilith, produced by women in Seattle, published Robinson’s Poor Black Women along with a Statement on Birth Control (which appears in Sisterhood is Powerful) by the group. The pieces appear under a headnote that indicates “the following two remarkable papers were sent to us by Patricia Robinson of New Rochelle NY and it is with her permission that we reprint them.” Clearly, Robinson saw herself as connected enough to women’s liberation to circulate her writing in its press. Robinson appears several times in late 1969 in Berkeley’s Spazm, a short lived, and until digitized by Reveal Digital, not widely available publication. The arrival of the piece in Berkeley may have come via Roxanne Dunbar of Cell 16 who is mentioned as sharing Robinson’s work in Berkeley. Robinson’s work was clearly circulating in mimeographed format as it appears on a reading list in the January 1969 issue of Voice of the Women’s Liberation Movement produced out of Chicago, but read nationally. Robinson’s work continued to be important as late as 1979 when Adrienne Rich cited it in Disloyal to Civilization.

While the other two black women who appear in the anthologies, Frances Beal and Maryanne Weathers are more easily traced through their subsequent activism that overlapped with women’s liberation, Robinson proved harder. I did find via Reveal Digital that Pat Robinson published a 1974 article “Historical Roots of Racism” in the newspaper edited by Beal for the Third World Women’s Alliance. Using searchable books, I was reminded by Katie King that Robinson remained connected enough to feminist movements that she appears in 1982 at the famed Barnard Scholar and the Feminist conference on Sexuality, aka the Sex Wars conferences, leading a workshop and in the anthology of that conference Pleasure and Danger. That then links her to another area I looked at to determine influence, academic conferences.

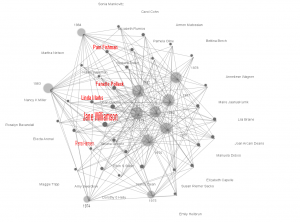

Conferences provided a common crossroads for many people in women’s liberation as it overlapped with the academic field we know as women’s studies. Barnard’s Scholar and The Feminist Conferences drew hundreds of women annually to a one day event focused on some of the biggest issues of the day. I originally intended to explore networks of presenters at the S & F but when I arrived in the archives I found to my delight complete registration lists typed in a format amenable to scraping. What an opportunity to look at another kind of community from its largest perspective! After digitizing and processing eleven years of registrations lists, I found that of the around 2000 unique names (out of a total of around 5000), the person with the longest history of participation was the librarian Jane Williamson (none of the names in red below are academics).

Like Robinson Wiliamson’s name appears frequently in citations of women’s studies texts. She edited or co-edited five books, ranging from Who’s Who and Where in Women’s Studies and the Women’s Alliance Almanac “a one-volume encyclopedia” to three important bibliographies of women’s studies. In other words, she produced the stuff community was built on in the days before the internet. She also started work at one of the first two journals of women’s studies,Women’s Studies Newsletter, straight out of Columbia library school, eventually becoming the managing editor, which is why she popped up in the top names I extracted using Stanford’s NLTK from the corpus that I received from JSTOR via the Data For Research program. Interestingly, given my use of feminist periodicals here as a dataset, she was also an early historian of them, authoring several articles for both popular and academic audiences. She also served as the librarian of the Women’s Action Alliance, Gloria Steinem’s sort of feminist consulting firm for lack of a better description, and set up Ms Magazine’s first library.

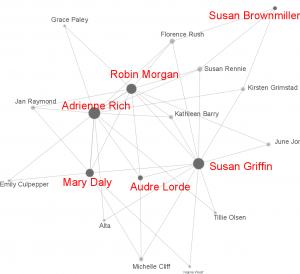

Librarians are truly relegate to the margins of scholarship, appearing generally only in the acknowledgements, which is in fact where I found Williamson again. Remember that Adrienne Rich alluded to Robinson in 1979. Rich was one of a cluster of authors on the periphery, academically speaking, of this thing called women’s studies developing in the 1970s. I took some important titles, starting in 1975 running up to 1981, digitized the acknowledgements, and pulled the names by hand into a spreadsheet. Of the 435 names, the common network reduces to this.

Of course Robinson does not appear here nor does Williamson, who was mentioned only by Robin Morgan. The question I’m left with then is what kind of network do I need to construct to capture not only the community of authors that we know influenced one another, but other people like Williamson, as well as Patricia M. Robinson, and the mostly nameless women she worked with in “the group” whose contributions are not easily captured in the network models we have. How do I weigh or weight contributions so that authors aren’t so privileged, which in a grassroots movement may misconstrue influence.

As always occurs in a digital project, the moment came when I left the “tools” behind and turned to intensely qualitative research. An online memoir by Chude Pam Allen, published in 2008, contains the information that Pat Robinson sought her out in 1967 to ask about Allen’s women’s liberation group in New York City (which may have been New York Radical Women). Robinson also gave Allen advice “to think in terms of class. Pat Robinson gave me a base to stand on, one that put the needs of poor Black women ahead of the rhetoric of the Black Nationalist Movement.”[3] This personal contact attests not only to Robinson’s involvements with radical women, but also to her importance for the development of radical feminism

When members of the Third World Women’s Alliance, like Beal and Weathers, marched in parades or participated in demonstrations, they became visible, quite literally, as part of that thing called women’s liberation while the protest letters and Freedom schools of the Poor Black Women’s Study Group, the name the group Robinson worked with published under, remained invisible, except for the traces they left in print. Yet their writing along with Beal and Weathers spread throughout women’s liberation. Perhaps no greater testimony to this exists than the Redstockings Women’s Liberation Archives for Action, 1940’s-1991 which “offers primary sources that place African American women among the movement’s earliest organizers, thus helping to dispel the myth that Black women generally either ignored or opposed Women’s Liberation. “ The Redstockings’ archives contain the early copies writings by Robinson and her group, as well as Beal and Weathers’ work, along with work by the only black member in the founding Redstockings, Celestine Ware, whose writing appears not at all in these anthologies because she herself had a book contract for Womanpower, which also came out in 1970.

What we really want here of course is a visualization that combines all the things, but I’ve resisted creating one for now.The complex historical questions of who gets counted when we count in histories of women’s liberation exists because data reduces people’s lived experiences to columns on a spreadsheet. What we place in those columns and how we count them though often reflects existing power hierarchies and reifies them. The challenge of the historian’s altmetrics is how to construct them so they resist.

8