while geographically Chicago seemed distant from the centers of what we now think of as the powerhouses of early radical feminism, Chicago played a pivotal role, both in disseminating early women’s liberation thought, but also as a position in between the movement “heavies” of DC and the radical feminists of New York. As socialist feminist, the Chicago contingent had a foot in both camps, insisting with the politicos on the primacy of material conditions, but seeing the radical feminists point of view when it came to centering women’s liberation.

In fact the fighting between the two factions is traceable via the Chicago publication Voice of the Women’s Liberation Movement (VWLM), the first national periodical of women’s liberation put out by Westside group member Jo Freeman, reveals divisions that emerged around the role of culture in justifying the need for an autonomous movement for and by women even before the movement coalesced.

The first skirmish occurred during the January of 1968 Jeannette Rankin Brigade, a coalition-led event of historical women’s organizations, such as the Women’s International League of Peace and Freedom (1915), newer, but still, well-established organizations like Women Strike for Peace, as well as women from the New Left.

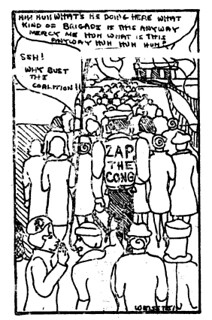

A cartoon by Naomi Weisstein in VWLM emphasized the dissent that emerged among various groups in the Brigade.

The conflict ensued when the New York Radical Women created a protest inside the protest that relied on agit-prop theater techniques. Organized largely by Shulamith Firestone, who had left Chicago for New York by that point, and Kathy Amatniek (later Sarachild), the event made use of the symbolic space of Arlington Cemetery to stage a mock funeral for “traditional womanhood” with the image of women’s role during war providing the “corpse.”

wives, mothers and: mourners; that is, tearful and passive reactors to the actions of men

The protest consisted of a funeral procession for

a larger-than-life dummy on a transported bier, complete with feminine getup, blank face, blonde curls, and candle. Hanging from the bier were such disposable items as S & H Green Stamps, curlers, garters, and hairspray.

The rallying cry “”DON’T CRY: RESIST ” linked the symbolic action to a desired political action.

However The Burial of True Womanhood* targeted women’s oppression as much as it aimed at ending the war.

Now some sisters here are probably wondering why we should bother with such an unimportant matter at a time like this. Why should we bury traditional womanhood while hundreds of thousands of human beings are being brutally slaughtered in our names… Sisters who ask a question like this are failing to see that they really do have a problem as women in America…that their problem is social, not merely personal..that we cannot hope to move toward a better world or even a truly democratic society at home until we begin to solve our own problems. … We must see that we can only solve our problem together.

While the sexist dismissal of the Brigade’s effort by the New Left was sadly predictable, the criticism from other women stung bitterly. Rather than the “sisterhood” called for in their action, NYRW was met with condemnation, particularly from D.C. women’s liberation activists who viewed the protest as “apolitical” and playing into the hands of men on the left who wanted to dismiss women’s liberation. Two high profile members of the nascent D.C. group, Pam Allen and Marilyn Webb, published accounts in the same issue of VWLM which reveal their profoundly different views of how women could achieve social change.*

Allen, who never mentions the Burial of True Womanhood, focuses instead on the many failures of the “radical women” at the Jeannette Rankin Brigade to capitalize on the excellent opportunity to organize “militant” women. “women … were interested in more than words. They were angry and wanted to ‘do something.’ ” The tenor of that observation, combined with her remarks that women “wanted action, not rhetoric” and an emphasis on the need to “channel their feelings into constructive action” implied a divide between “doing” and “talking” with a marked preference for the former. Protests that centered of rhetorical action and that invoked emotions, like The Burial of True Womanhood occurring far away from the center of power, at Arlington Cemetery in Virginia, were a far cry from Allen’s preferred “organizing civil disobedience-carrying signs in defiance of a police edict and confronting Congress on the Capitol steps.”

Marilyn Webb’s article, although ostensibly a “call for a spring conference” also invoked the Brigade. Like Allen ,Webb focused on the need to organize.

In order for women to begin-to develop political consciousness and the power necessary to act on such a consciousness, we must organize.

The use of the word “consciousness” links Webb’s remarks to a debate already emerging within women’s liberation. Consciousness-raising, “talking” as a means of developing greater awareness of women’s oppression, represented one strand of organizing women. Because images of women functioned to oppress women, women need to first raise their consciousness about that oppression as a crucial step in organizing politically. While this view is most strongly associated with NYRW, in this issue of VWLM a Chicago group explained its value.

The Women’s Radical Action Project… formed last fall to discuss radicalism and women.

At first our discussions were very groping. … as we gained a group identity and common understanding we could probe more deeply into such questions as the role of women in the radical movement the conflict between an identity as a women and as a person, and the relationship between issues of women’s liberation and radical action and education. … We also want to organize other women around issues that will make them realize their identify as articulate, intelligent, competent and political human beings.

The idea that discussion provided the “action” that led to answers to the key questions facing women’s liberation, and that the goal was to organize women to talk, to help women become more articulate, stood in stark contrast to Webb’s plan.

We hope to hold at least four regional organizational conferences of radical women this Spring to begin to develop programs and analysis. The conferences should set up by each region so that they reflect the interest of each region, but we would hope to share working papers and perhaps some speakers.

While Webb acknowledged the need for “dialog” and “to talk to people about our concerns” and for radical women “to say “no” to the system” her preference is clearly for organizing, ends with the plea “we as radical women have to organize ourselves.” In contrast, the Chicago women ended their article on the note “These are just some ideas; we still need.to do a lot of talking. … But we’re organized, and we’re growing.”

Firestone’s analysis of the events at the Brigade is ironically quite similar to Webb and Allen’s

It was a great moment. But we lost it. … one good guiding speech at the crisis point which illustrated the real causes underlying the massive discontent and impotence felt in that room then, would have been worth ten dummies and three months of careful and elaborate planning

However, Firestone’s understanding of the “real causes” and the conclusions she draws are quite different.

We confirmed our worst suspicions, that the job ahead, of developing even a minimal consciousness among women will be staggering

Firestone sees the “talking” and “doing” as related in her defense of “dramatic action” as sometimes “most effective.” Her notion of “consciousness” rests on the analysis represented by the Burial’s desire to spur “organizing as women to change that definition of femininity.” Changing definitions of femininity, such as the offensive cover of Rampart that “reduced women to two tits with no head” and “perpetuates their status as sexual objects … the basic form of oppression women must struggle against” meant that women’s liberation must challenge culture, images and words, in protests like the Burial of True Womanhood.

+++++++

* to the historians ear, the name of the protest, and its content, immediately call to mind Barbara Welter’s 1966 article on the Cult of True Womanhood. I’ve not been able to establish a definitive connection between this article and the title of the protest.

**Pam Allen, RADICAL WOMEN AND THE RANKIN BRIGADE, March 1968, Vol 1, no 1, 3 and Marilyn Salzman Webb, CALL FOR A SPRING CONFERENCE, March 1968, Vol 1, no 1, 4. Echols discusses the articles that evolved out of these pieces and were published in New Left periodicals, The Guardian and New Left Notes, because her primary focus is the split between radical women and the New Left. I’ve chosen to focus on the original articles in order to reveal the conversations that occurred among radical women.